Obesity is a chronic disease. Get over it.

Obesity is defined as an excessive accumulation of fat mass compared to lean mass, both in absolute terms and in how it is distributed across the body. To assess whether someone is overweight or obese, doctors typically use the Body Mass Index (BMI)—based on weight and height—and waist circumference, which reflects the build-up of visceral fat, the most dangerous kind for our health.

The global rise of obesity is one of the biggest public health challenges of our time. It is strongly linked to chronic conditions such as diabetes, heart disease, and certain types of cancer. According to the World Health Organization, by 2022 there were already 2.5 billion overweight people, of whom 890 million were obese. And no, things are not getting any better—the numbers keep climbing.

Obesity has long been recognized as a chronic, multifactorial disease. It’s far more than just “Why don’t you eat less? You’re just lazy!”

While overeating is the main driver of weight gain, we now know that obesity is shaped by a combination of biological, psychological, and social factors—not simply by individual willpower.

How the hunger–satiety system works

In normal conditions, when the body uses more energy, appetite increases; when energy use drops, appetite decreases. This helps us maintain body weight within a relatively stable range over time. The system is finely tuned by a sort of internal “lipostat”—a mechanism that monitors fat storage and adjusts food intake and energy expenditure accordingly.

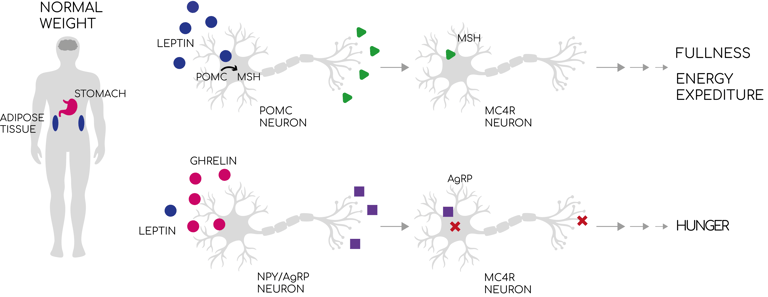

One of the key systems here is the leptin–melanocortin pathway. Leptin is a hormone released by fat cells that tell to the brain how much energy is stored. High leptin levels tell the brain that reserves are sufficient, reducing hunger and stimulating energy use.

In the brain, different groups of neurons respond to these signals. POMC neurons promote satiety, while NPY and AgRP neurons increase appetite. When leptin is high, POMC neurons are activated, leading to the production of α-MSH, which binds to MC4R neurons to reduce food intake and boost energy expenditure. When leptin is low, another hormone—ghrelin, produced by the stomach during fasting—activates NPY/AgRP neurons, driving hunger through inhibition of MC4R neurons.

In short, the brain continuously integrates a flood of hormonal signals to balance hunger, fullness, and energy use.

Why, then, do we gain weight?

Here comes the bad news: our weight-regulation system evolved to help humans survive in prehistoric times, when food supplies alternated between plenty and scarcity. In that context, those who could store more energy as fat had a survival advantage. In other words, we evolved to gain weight, not to lose it.

But evolution isn’t the only factor. Obesity arises from a mix of modifiable factors (like diet and lifestyle) and non-modifiable ones (like genetics).

Genetics: Mutations in genes regulating body weight can have dramatic effects, though genetic obesity is relatively rare.

Modifiable factors: These account for most cases of obesity and include high-calorie diets, sedentary lifestyles, poor sleep, certain medications, social conditions, stress, prenatal environment, gut microbiota, and especially the widespread availability of industrially processed foods.

The basic rule of weight gain is simple: if you take in more calories than you burn, you store fat. But why has obesity skyrocketed since the 1970s? Did millions of people suddenly got an eating disorder?

Industrialization didn’t just change the nature of food—it also reduced daily physical activity. Our ancestors spent their days in fields, working hard, and came home to simple meals: vegetable stews, legumes, bread with olive oil. Meat was a rare luxury, fish available mainly to coastal communities. Today, our food environment looks very different.

We are surrounded by ultra-processed foods: chicken nuggets from chickens that never saw sunlight, sugary fruit snacks, brightly packaged sauces, and other products that sell the idea of being healthy but are anything but. These foods are engineered to be hyper-palatable, loaded with sugar, fat, and salt—potentially triggering addiction-like behaviors. Over time, regular consumption may dull the brain’s sensitivity to their effects, pushing people to eat more for the same sense of reward.

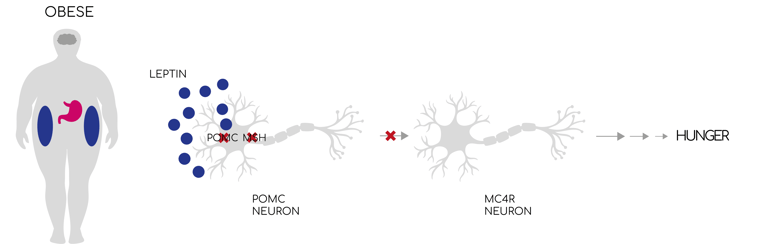

On a hormonal level, this leads to leptin resistance: even though leptin levels rise with fat mass, the brain stops responding to it. Satiety signals are blunted, and stopping eating becomes far more difficult.

Sleep deprivation lowers insulin sensitivity, decreases leptin, and raises cortisol and ghrelin, all of which promote hunger.

Besides, healthy foods like fresh fruit and vegetables are increasingly expensive, while cheap, calorie-dense fast foods remain widely accessible.

Excess maternal weight gain or gestational diabetes can predispose the child to obesity later in life.

The community of microbes in our intestines plays a key role in how we store and use energy. A more diverse microbiota is generally protective against obesity, and its composition is influenced by diet, birth method (vaginal or cesarean), breastfeeding, and antibiotic use in early life.

So, is obesity really just a matter of choice?

Obesity is the outcome of a complex web of influences, from evolution and genetics to modern lifestyles and social factors.

So next time someone says it’s just about “willpower,” ask yourself: are we really the ones choosing?

BIBLIOGRAPHY AND RESOURCES:

- Juul, F., Martinez-Steele, E., Parekh, N. et al. The role of ultra-processed food in obesity. Nat Rev Endocrinol (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41574-025-01143-7

- Shim J. Ultra-Processed Food Consumption and Obesity: A Narrative Review of Their Association and Potential Mechanisms. JOMES 2025;34:27-40. https://doi.org/10.7570/jomes24045

- Masood B, Moorthy M. Causes of obesity: a review. Clin Med (Lond). 2023 Jul;23(4):284-291. doi: 10.7861/clinmed.2023-0168. PMID: 37524429; PMCID: PMC10541056.

https://data.worldobesity.org/rankings/?age=a&sex=m

https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight WHO incidence of obesity

COVER IMAGE CREDIT: Dancer at the bar, Botero